Many people assume night vision cameras can see through windows like regular daylight cameras. That’s a common mistake-and it can cost you real security. If you’ve ever set up a night vision camera inside your home to watch the driveway, only to see a blurry reflection or a glowing pane of glass instead of the person outside, you’re not alone. The truth is simple: night vision doesn’t work the same way through glass as it does in open air. And the reason has everything to do with physics, not camera quality.

Not All Night Vision Is the Same

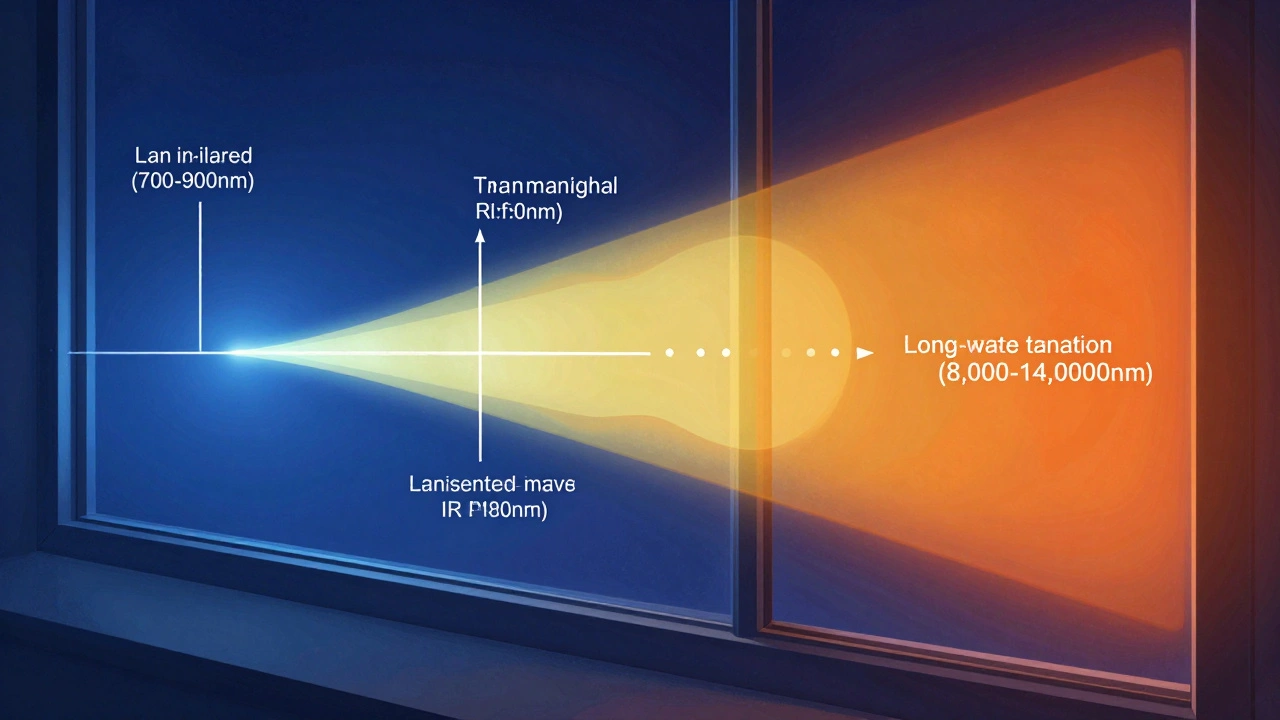

There are two main types of night vision technology used in consumer and professional gear: image intensifiers and thermal imagers. They work in completely different ways, and that changes everything when it comes to glass.Image intensifiers (like Gen 3 tubes in devices such as the L3Harris AN/TVS-5) don’t create heat images. Instead, they amplify tiny amounts of visible and near-infrared light-think moonlight, streetlights, or the faint glow from an IR illuminator. Standard glass transmits this kind of light pretty well. In fact, about 91.5% of visible light passes right through a typical window. Near-infrared light (around 700-900nm) also gets through with only 8-12% loss. So if you’re using a digital night vision camera with an IR LED (like the AGM Redcat 5S), you’ll often get a usable image through a window… as long as you deal with reflections.

But here’s the catch: glass reflects infrared light. If your room is lit up and the outside is dark, your camera will mostly capture the glow of your own living room bouncing off the glass. That’s why users on Reddit and HuntingNet report seeing their own face or TV screen instead of the backyard. The fix? Turn off indoor lights, use a black cloth around the camera lens to block stray light, or angle the camera at 30 degrees to reduce reflection by up to 60%.

Then there’s thermal imaging. Devices like the FLIR Boson 640 or Pulsar Thermion 2 XQ35 detect heat-long-wave infrared radiation (8,000-14,000nm). And this is where glass becomes a wall, not a window. Standard window glass is made of soda-lime silica, which blocks nearly all thermal radiation. According to Raythink Technology’s 2023 analysis, a 3mm pane of glass lets through just 0.3% of 10,000nm infrared. That’s not a glitch. It’s science.

When you point a thermal camera at a window, you’re not seeing what’s outside. You’re seeing the surface temperature of the glass itself. If the window is cold, it shows as a dark rectangle. If it’s warmed by sunlight or indoor heating, it glows like a dull heater. FLIR’s own application note AN-2023-017 confirms this: thermal imagers see the glass, not through it. Users who’ve tried to spot deer, intruders, or pets through windows with thermal scopes consistently report the same result: a blank, uniform surface with no detail behind it.

Why Thermal Imaging Fails Completely Through Glass

The reason isn’t about camera sensitivity. It’s about molecular structure. Glass molecules absorb infrared wavelengths longer than 2,500nm. Thermal cameras rely on wavelengths between 8,000-14,000nm. That’s like trying to shine a flashlight through a brick wall and expecting to see the other side. Dr. Robert D. Fiete from Rochester Institute of Technology put it plainly: “Glass molecules resonate at frequencies that absorb thermal infrared radiation, making standard windows opaque to thermal imagers.”There are exceptions-but they’re not practical for most users. Germanium or zinc selenide windows can transmit thermal radiation, which is why military vehicles like the AN/PAS-13 have special IR-transparent viewports. But those materials cost over $1,200 per square foot. You won’t find them in your home. Even thin glass under 0.5mm (used in some drone cameras) only lets through a tiny fraction of heat signature-and it’s too fragile for windows.

Some companies claim their “IR-transparent” glass works. PPG Industries launched OptiView IR in late 2023, promising 85% transmission of 8-12μm wavelengths. But at $42 per square foot (compared to $5 for regular glass), it’s only used in high-end military or research facilities. For home users? It’s not an option.

What Happens When You Try to Use Night Vision Through Windows

Real-world results match the science. Amazon reviews for popular night vision cameras like the AGM V500 Pro show consistent complaints. One top reviewer wrote: “Useless for indoor surveillance through windows-shows only reflections and glass temperature.”On Reddit’s r/NightVision, users share their frustrations. One person tried using a Pulsar Thermion 2 from inside their truck and saw nothing but the windshield’s heat signature until they cracked the window. Another removed the Low-E coating from their cabin window with a razor blade and suddenly spotted coyotes at 75 yards. Low-E coatings, designed to save energy, are especially bad for night vision-they reflect up to 25% more infrared than plain glass.

Military veterans on Soldier Systems confirm this too. Special Forces operators are trained to open vehicle windows by at least 2 inches before deploying thermal sights. The manual doesn’t say “adjust settings.” It says “open the window.”

How to Actually Monitor Outside Through Windows

If you want to use night vision to watch your yard, porch, or driveway from inside your home, here’s what works:- For image intensifier or digital night vision: Turn off all indoor lights. Use a black curtain or cloth to block ambient light around the camera lens. Angle the camera 30 degrees to the glass. Add a nano-coated anti-reflective film like ASCENDENT Group’s ClearView ($199) to cut reflections by 35%.

- For thermal imaging: Don’t rely on windows. Install an exterior-mounted thermal camera in a weatherproof housing. This is how 78% of commercial security systems handle it, according to Security Today’s 2023 report. Brands like FLIR and Hikvision make models designed for outdoor use with built-in IR illumination and heat management.

- Hybrid solution: Use a dual-sensor camera that combines visible light, near-IR, and thermal. New systems like Lynred’s multi-spectral tech (patented in July 2023) can infer objects behind glass by analyzing thermal gradients-but it’s still experimental and not yet available in consumer gear.

Why This Matters for Home Security

This isn’t just a technical curiosity. It’s a security blind spot. The National Institute of Justice found that law enforcement agencies have 41% higher false-negative rates when using thermal cameras through windows. That means they miss threats because they think the camera is working. In homes, it leads to false confidence. People install cameras near windows, assume they’re covered, and later find out they captured nothing.The global night vision market hit $5.82 billion in 2023. But 63% of indoor security camera installations require exterior mounting because of this glass problem. That adds an average of $320 per unit in extra labor and hardware costs. If you’re trying to cut corners by placing your camera inside, you’re not saving money-you’re risking your safety.

What’s Next? The Future of Seeing Through Glass

Researchers are working on solutions. The European Defense Agency’s “Project Crystal Eye” is testing electrochromic glass that becomes transparent to thermal wavelengths when electrified. Prototype tests are scheduled for late 2025. FLIR is also developing algorithms that reconstruct thermal scenes behind glass by analyzing multiple camera angles. But don’t expect these to hit consumer markets soon.For now, the rule stays simple: thermal imaging sees the glass. Image intensifiers see through it-if you manage reflections. There’s no magic setting, no firmware update, no expensive lens that changes the physics of glass. The best way to see what’s outside? Put the camera outside.